The earliest known form of the name „Rübezahl” (Krkonoš, Karkonosz, Liczyrzepa, Duch Gór) is Martin Helwig’s 1561 RübenƷal in his Landkarte Schlesiens, accompanied by the now-famous image reproduced below.

Subsequent versions include Rübezal, Ribezal, Riebenzahl etc.

Today the most widespread spelling is Rübezahl.

The exact meaning of the name has long been a source of controversy, but in reality besides the obvious „He Who Counts Turnips” – which to me seems so foolish a name for a demon that I dismiss it right away – all the other propositions are based on just two circumstances:

1. that Rüben- is derived from Riephen as in Riphaei Montes (Riphean Mountains), a name used by Ptolemy and identified with the Karkonosze / Riesengebirge / Giant Mountains, also known as the AΣKIBOYPΓION OPOΣ (Askiburgion oros) (a nice presentation in Polish

here); and that

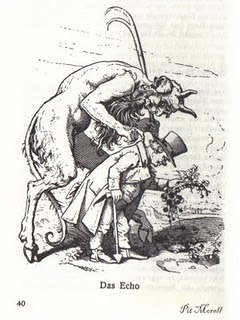

2. -ʓal has to do with Zagel = tail, implying „devil” or „demon”, as can be seen in the image above.

I would like to present two other explanations, one by a famous author but (the proposition) seemingly unknown to the general public, the other by myself. On top of that, I will hint at a possible revolutionary – and interconnected with the previous one! – theory on the name Karkonosze – which may possibly reveal who Rübezahl really is.

„Pflanzen der Koenigin Isis”: Sergius Golowin and his theory on the name Rübezahl

In his 1973 Die Magie der verbotenen Maerchen [Magic of the forbidden fairy tales, 6. Auflage, Gifkendorf 1989] (thanks to Theater der Zerbrochenen Fenster’s Klaus Eichner in Bluecherstrasse, Sudstern, Kreuzberg, for that), the phenomenal and fundamental Sergius Golowin quotes from H. Zoernig’s Arzneidrogen, Leipzig 1909:

„Neben den Nachtschatten-Gewaechsen treffen wir als Bestandteil der geheimnisvollen Salben, die den Hexen angeblich ihre Seelenreisen in ihr Zauberreich ermoeglichten, vor allem auch den blauen Eisenhut„

and explains:

„In seinem wissenschaftlichen Namen Aconitum nepellus stammt der erste Teil vom Griechischen Wort akone, Gebirge – vom zweiten vernehmen wir: «Napellus ist das Diminutiv von Napus, lateinisch Rübe, das heisst Wurzeln wie kleine Rüben»”.

Then he attributes the Eisen- in Eisenhut to „die weise Frau «Eysen»”, from where he proceeds to Isis – which coincides interestingly with my theories on the origin of the name Izera / Iser – to say:

„In den alten Mittelmeerkulturen behauptete man, die Hekate, die grosse Meisterin aller Hexen, habe den gebrauch des Eisenhutes eingefuehrt, und die Zauberin Medea soll ihn im Skythenlande, also bei jenen Voelkern, die nun einmal fuer die Griechen Meister der Drogenkuenste waren, gepflueckt haben” (p. 37).

Perhaps it is time to introduce the mighty Aconitum:

[Mała Kamienica]

„W starożytności wykorzystywany był jako zabójcza trucizna, w Europie w okresie renesansu był najczęściej stosowaną trucizną.

W średniowieczu używano go do zatruwania strzał i mieczy.

Ludowa nazwa tojadu nawiązująca do jego trujących właściwości to „mordownik”, zaś Pliniusz Starszy, również nawiązując do jego trujących własności nazywa go „arszenikiem roślinnym”.

(…)

Tojadem otruto podobno Arystotelesa, zaś według Dioskurydesa jad tojadu jest tak silny, że zabija skorpiony.

Według mitologii greckiej tojad powstał ze śliny strażnika Hadesu – psa Cerbera o trzech głowach.”

W tym momencie nie mogę sobie odmówić zreprodukowania jednego ze wspaniałych suchorytów

Pita Morella ilustrujących tom Golowina:

[Pit Morell, Das Echo, Oeuvre-Verz. 599, in: S. Golowin, Die Magie, op. cit., p. 40]

Continues Golowin:

„Rübe ist aber nun einmal fuer die Sprache «die allgemeine Bezeichnung fuer die bekannten Kulturpflanzen mit fleischiger, spitzzulaufender Wurzel, besonders fuer die Wurzel selbst»” (p. 88).

And then, crucially:

„Als «Rübe» verstand man, wie wir schon sehen konnten, sogar den Eisenhut, die magische «Blaue Blume». Ein litauischer Name des Bilsenkrautes lautet pometropes, wobei dieses Wort aus pometis = epileptischer Anfall (also aus einer Anspielung auf die Wirkung dieser Hexendroge) und rope = wiederum Rübe, zusammengesetzt ist [footnoted to M, 2, 928 = H. Marzell, Woerterbuch d. deutschen Pflanzennamen, Leipzig 1943]. Die ebenfalls giftige Zaun-Rübe erscheint gar in vielen Mundarten fast wie die Rübe an sich. Wir finden etwa Ausdruecke wie Wilde Rübe, Roemische Rübe, Faule Rübe, Hexengrübe, in der Schweiz Hag-Rüebli: An Zustaende, hervogerufen durch ihre Wurzelgraebern und Hexen bekannten, mit denen der Alraune verglichen sehr giftigen Wirkstoffe (also an Tollheit und naerrisches «Rasen»), erinnern Ausdruecke wie Toll-Rübe, Ras-Rübe oder polnisch durna rzepa = Narren-Rübe” [footnoted to M, 1, 684, op. cit.].

„Bieluń dziędzierzawa ma bardzo wiele nazw potocznych i ludowych: pinderynda (kieleckie), dędera (wielkopolska), denderewa (Mazowsze), ogórczak (środkowe Mazowsze), tondera, pindyrynda (Śląsk), cygańskie ziele (białostockie), świńska wesz (sandomierskie), bieluń podwórzowa, dendera, dendrak, durna rzepa. Ze względu na jego narkotyczne i trujące własności dawniej nazywano go także czarcim zielem, diabelskim zielem, trąbą anioła”…

Golowin nochmal:

„«Tolle Rübe» (durna ropa) [sic! - a slip? shouldn't it read durna rzepa? - ed.], «Böse Rübe» (pikt-rope) ist bei den Litauern das «Krainer Tollkraut», das Nachtschatten-gewaechs Scopolia carniolica – das von ihnen ebenfalls zu allerlei «Belustigungen» und fuer «rauschartige Zustaende» verwendet wurde” [G. Hegi, Illustrierte Flora v. Mitteleuropa]. Auch die Tollkirsche heisst im Mecklenburgischen Roewerint = ebenfalls in Anlehnung an Röwe, Rübe, und zwar «wegen des dicken walzenfoermigen Wurzelstockes».

Sogar der Märchenname Rapunzel scheint zum lateinischen Wort rapum, Rübe zu gehoren!” – !

As for the

Scopolia, we read, true to life, in the

English wikipedia: „ It is poisonous as it contains abundant quantities of tropane alkaloids, particularly atropine.

The quantity of atropine is the highest in the root„…

Never one to spoil fun, I leave you to locate your own copy of Sergius Golowin’s Magic of the Forbidden Fairy Tales and do your own translations, the conclusions of which may differ from those I imply.

Nonetheless, Golowin seems to suggest that the crucial Rübe refers to medicinal/witch/magic/psychoactive/religious plants which are a lost link in the history of the European civilisation, and that Rübezahl has to do not with turnips but with mind-altering rituals of the old.

Of course, placing this „Master of (Ritual) Plants”, or – perhaps – „Speaker of (Ritual) Plants – because it is not -zal or -zahl but Erzähler! – up in the mountains can only mean one thing: that the mountains are the place where the rituals are held, not where the plants are collected! Who has ever gone up in the high and stern Riesengebirge to collect plants?! Everyone knows that nothing grows there, except mountain pine and stones…

To recapitulate: the root -Rübe- refers to the ritual/magic/psychoactive/mind-altering/witchcraft/medicine plants and Rübezahl is „der beruehmte Kobold, Berggeist, Hexenmeister, Gnomen-Herrscher im Riesengebirge” – the master of the ceremonies, to put it simple.

My theory

While I find Golowin’s argument plausible and appealing, I still cannot find in it a CONCLUSIVE link between the word Rübe and the medicinal plants.

My theory is so simple I’m surprised no one has thought of it yet:

The outstanding Polish geologist Michał Sachanbiński writes very clearly in his 1979 Kamienie szlachetne i ozdobne Śląska [The precious and decorative stones of Silesia] (Chapter 4. Śląskie kamienie szlachetne (jubilerskie): 4.1. Korund i jego barwne odmiany (rubin i szafir): 4.1.1. Korundy w złożach pierwotnych):

„Największe pierwotne wystąpienie korundu w Polsce znajduje się w Karkonoszach, gdzie w pegmatytach z okolicy Wilczej Poręby od dawna notowano pojawienie się kilku[-]centymetrowych kryształów korundu. Szczególnie znanym punktem, gdzie w paragenezie z minerałem dumortierytem występowały białe lub bladoniebieskie korundy (szafiry) do 5 cm, są Krucze Skały w Wilczej Porębie”…

(4.1.2. Korundy w złożach okruchowych):

„Szczególnie duże koncentracje minerałów ciężkich notuje się w żwirach doliny Izerki i na Hali Izerskiej, a także w bocznym dopływie Izery – Jagnięcym Potoku. Oprócz izerynów, czerwonych i czarnych spineli, cyrkonów, hiacyntów i in. znajdują się tam również korundy czasem z widocznym zjawiskiem asteryzmu”… (s. 60)

Does it really stretch the imagination to see

Rubin + Zahl? Weren’t die

Walen / Edelsteinsucher / Venetianer/ Walonowie / Walończycy involved precisely in that – counting precious stones? Just as Hermes / Mercury guarded over Greek merchants and tradesmen in the Aegean, so th

e Rubin Counter made sure the Askiburgic prospectors like

Johannes Prätorius were safe…

Final and fundamental proposition

But this was nothing compared to what I am going to say now.

The starting equation is simple – shattering – revelational – explosive – revolutionary – and so convincing I must say it again: why has no one noticed this yet?!

Here it goes:

Karkonosze / Krkonoše = Cerconossios = Cernunnos!!!

Unconvinced? Look at this:

Heed this:

The Proto-Celtic form of the theonym is reconstructed as either Cerno-on-os or Carno-on-os.

Do I hear you saying Krkonoš?

Well, I’ll leave it at that for today. Have fun thinking this over!